Вот текст

The Island Visit

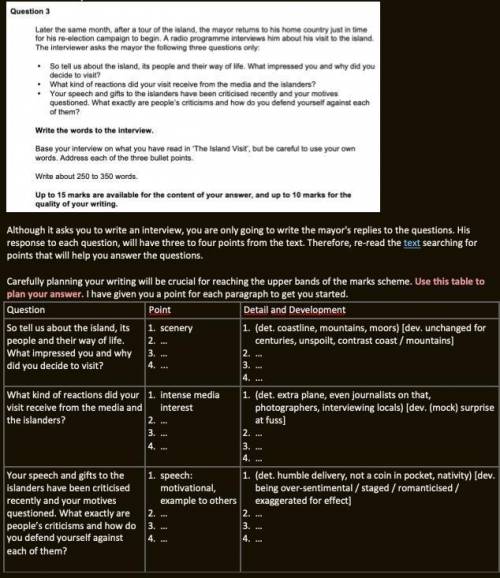

In this passage, a journalist describes the occasion when the mayor of a large city in a wealthy foreign country returns for the first time to visit the small island he left when he was a baby.

The car bringing the big city mayor – a fine limousine borrowed for the occasion – stopped at the entrance to the village. Its occupant got out, amid the clamour of applause, flashing of lenses and clash of the band, into a confused mass of policemen, journalists, inquisitive spectators, infinite numbers of cousins, shepherds, women, and in fact the whole 4,000 inhabitants of the island who were waiting for him. The village boys crowded round. Pushing and yelling to each other, they shouted, ‘Let’s touch the car; then we’ll become rich and famous too!’

The car had only just arrived and had already become a relic, a thing holy and miraculous, which if merely touched promised pathways to paradise. Immediately his press officer had announced it, the mayor’s visit was, for islanders, a fabulous adventure, a mythological occurrence. I don’t know how conscious he was of this, or the real reasons for his journey – an affectionate curiosity to become acquainted with his own native place and pay homage to the memory of his parents, a quest for popularity, a wish to do something that would please his electors, or some combination of these things? If he’d been born in a large town, his journey would be no more than ordinary political news. Instead, the whole tale unfolded under full media glare.

Seasoned journalists had already made an assault several days beforehand on all possible means of transport from the mainland. With beginners’ luck, I’d found myself unexpectedly on an extra plane in which it happened the esteemed mayor himself was travelling. We’d arrived at the island’s airport to the first troop of officials, photographers and a great quantity of the mayor’s more persistent cousins, come from all parts to greet their illustrious relation. The mayor was immediately dragged off into the whirl of the official reception. Beset by some of the shyer members of the mayor’s clan who’d taken me for an intimate friend of their grand relation and who, displaying their identity cards and documents, begged me to introduce them to him, I’d got into my taxi with some difficulty.

At first, the road had passed along the most splendid coastline floodlit by sunshine. Men and women worked at vegetable gardens and fishing nets, a cinematic panorama of agile forms in action. Endless fleets of painted carts, perambulating shops gaily decorated, rolled along the road navigating the sea of people. A cart beyond repair lay beached belly-upwards at the roadside, its intricately-carved merchandise laid out like entrails in the sun. Beyond, the road turned inland toward the mountains, the landscape changing to immense bare moorlands, solemn and desolate. Sheep blocked our road ahead. Their ancient shepherd leaned on his staff and regarded us quietly. The history of the mayor’s village to date had been merely prehistoric.

Like detectives in some large-scale inquiry, journalists questioned door-to-door with a sort of mania. They wanted everyone’s names, ages, jobs and family details, and of course their degree of relationship to the mayor. One old woman, a daughter of one of the witnesses to his birth, assured me, ‘The mayor was born here, in this very dwelling. I gave the family some cheese to eat on their voyage.’ She added, ‘They were poor and hadn’t any money.’

A journalist with a moustache interrupted at this moment, demanding like an examining magistrate, ‘What do you hope the mayor will do for you?’

‘Anything is possible,’ said the old woman. ‘Many things are needed: a hospital, a school.’ She answered just to satisfy the journalist, in reality not asking for, hoping or expecting anything.

It was difficult now to get near the action owing to the great buzzing crowd paying faithful homage. On broad strips of cloth was written, ‘Welcome in your nice country’. How many eyes, how many hands, how many countless individual tasks paused to hear the visitor speak from a purpose-built platform overlooking the street!

He spoke humbly about his nativity, his father and mother, saying, ‘I’m the son of a poor shoemaker who left without a coin in his pocket.’

‘This all goes to show that it is possible,’ he concluded.

Everybody was happy.

Finally, it was announced that the mayor would give a considerable sum to his eldest cousin’s old people’s charity and a larger sum still to the commune in order that public baths and a commemorative statue might be constructed in the village.

I couldn’t help wondering at the divine uselessness of such gifts.

Ответы

Показать ответы (3)

Другие вопросы по теме Английский язык

Популярные вопросы

- Сделайте краткое сочинение на тему Конституция Н. Муравьева...

1 - При диссоциации кислот в качестве катионов образуются только: * Вариант 1 OH- Вариант...

2 - 3. В первой вазе было в 5 раз меньше тюльпанов, чем во второй. Когда в первую вазу...

3 - Сделайте по группам 1 и 2 ...

2 - задание 5ғ класс! Make 5 sentences with new words: (составьте 5 предложений с новыми...

2 - Найдите сумму или разность двух дробей. В ответе указывайте дробь в формате: числитель/знаменатель....

3 - (x^2-16)(x^2-x-2)(X+2) 0...

1 - решить Ex. 32. Put the words in the right order to make sentences.1) city - the...

3 - Уберите корень из знаменателя...

1 - мне 13 лет , через месяц, рост 146 , это норм? , просто уже ревную к росту однколов...

1